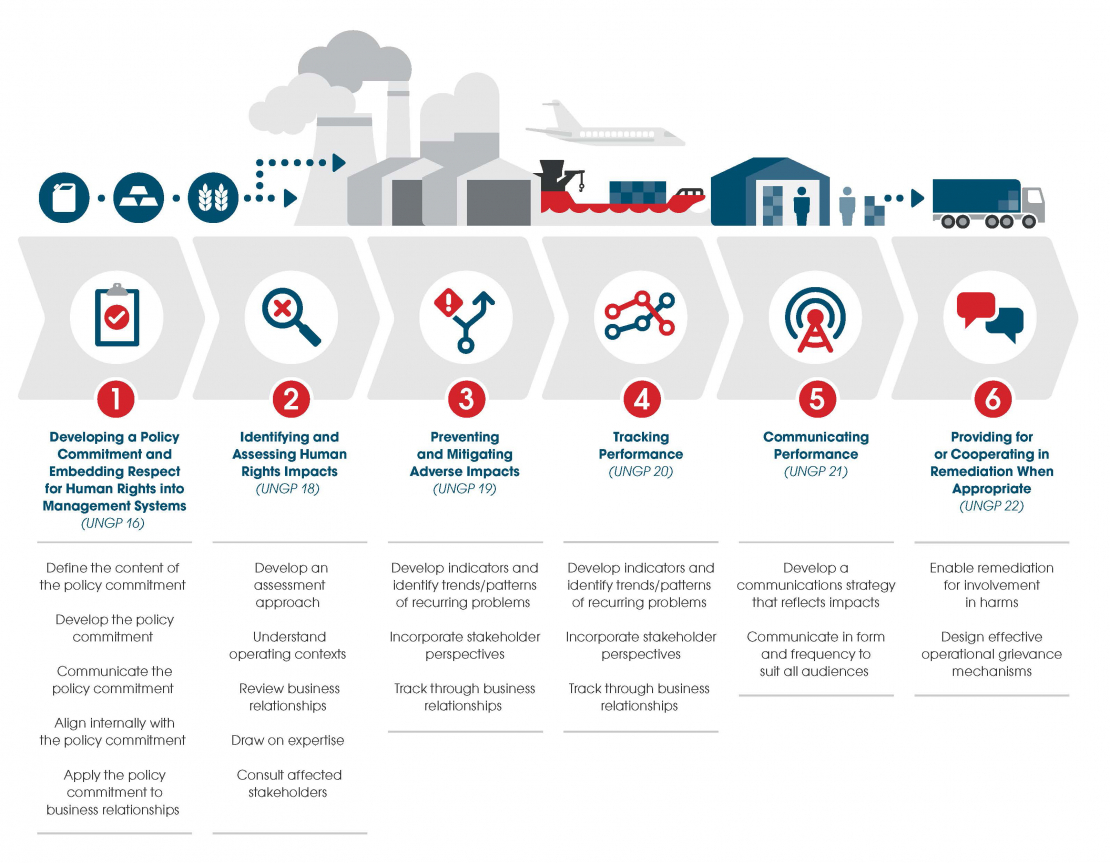

Key Actions

iii. Use leverage with business partners

The Commentary to UNGP 19 states that:

“Where a business enterprise contributes or may contribute to an adverse human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the greatest extent possible. Leverage is considered to exist where the enterprise has the ability to effect change in the wrongful practices of an entity that causes a harm.”

In other words, “leverage” is essentially about a company’s ability to get another organisation to take actions to address its own negative impacts on human rights. A common example concerns a company’s supplier which may be found to have abused the rights of its workers. How can the company positively influence its supplier in such a case?

The boxes below highlights different categories of leverage and consider how commodity traders may use business contracts as a form of leverage in business relationships.

Definition Categories of Leverage

A Shift Project publication proposes five categories of leverage:

- Traditional commercial leverage: leverage that sits within the activities the company routinely undertakes in commercial relationships. Specific means may include: contracts; audits; bidding criteria; questionnaires; incentives.

- Broader business leverage: leverage that a company can exercise on its own but through activities that are not routine or typical in commercial relationships. Specific means may include: capacity building; presenting a unified voice from each business department; referencing international or industry standards;

- Leverage together with business partners: leverage created through collective action with other companies in or beyond the same industry. Specific means may include: driving shared requirements of suppliers; bilateral engagement with peer companies.

- Leverage through bilateral engagement: leverage generated through engaging bilaterally and separately with one or more other actors, such as government, business peers, an international organization or a civil society organization. Specific means may include: engaging civil society organizations with key information; engaging multiple actors who hold different parts of a solution.

- Leverage through multistakeholder collaborations: leverage generated through collaborative action, collectively with business peers, governments, international organizations and/or civil society organizations. Specific means may include: driving shared requirements of suppliers; using convening power to address systemic issues.

Example Business Contracts as an Example of Leverage

Human rights due diligence requirements should be an integral part of contracts and address questions such as:

- who has responsibility in the relationship for addressing human rights risks and reflecting this in legal agreements?

- what expectations are set to ensure prevention and mitigation of adverse human rights impacts?

- how will such steps be monitored (e.g. through internal monitoring systems of the producer, through on the ground assessments by the trader, or through third part on-the-ground audits by specialised auditing firms) and discussed with business partners over time?

Example: Including human rights clauses in supply chain contracts

While the expected behaviour of suppliers with respect to human rights can be set out in a code of conduct or a similar document, the inclusion of human rights clauses directly in the purchase contracts themselves can be equally important. First, it can ensure that where buyers are responsible for human rights impacts at the supplier level (such as where the buyer is placing a high volume of orders at the last minute), the buyer will work with the supplier to remediate or prevent any harms. This demonstrates a clear commitment by the buyer that it will not undermine the human rights performance of the suppliers. Secondly, by sharing the responsibility for preventing human rights harms between suppliers and buyers through contractual provisions (in accordance with the human rights due diligence principles in the UN Guiding Principles), it cements the due diligence processes and ensures that any termination of contract or exit is done responsibly.

The American Bar Association developed a model set of human rights due diligence clauses in supply contracts in 2021. The model clauses are only intended to be used as a guide for in-house counsel who want to align supply chain contracts with the UN Guiding Principles. They were developed through a multi-stakeholder process with commercial lawyers, business bodies and human rights lawyers.

Example Leverage Together with Business Partners

Revolving credit is a line of credit where the customer pays a commitment fee and is then allowed to use the funds when they are needed.

A trade finance bank and a trading company active in the chocolate value chain recently announced the extension of the trading company’s revolving credit facility. They communicated that the applicable credit margin would be linked to the company’s sustainability performance and rating, thus encouraging the company to improve its sustainability performance.

The trading company’s sustainability programme includes four targets that it expects to achieve by 2025 and that address the biggest sustainability challenges in the chocolate supply chain: child labour, farmer poverty, its carbon and forest footprints and sustainable sourcing.

In terms of assessing the performance of business partners, the UNGPs stress that a company should prioritise those relationships where the severity and likelihood of potential human rights impacts is greatest (see commentary to UNGP 17, right). This prioritisation might focus on suppliers/contractors:

- active in locations where there are known human rights risks, such as limits on the right to form and join a trade union or poor enforcement of labour laws;

- with a known track record of poor performance on human rights;

- providing key products or services that themselves pose risks to human rights (for example safety or health hazards);

- lacking capacity to assess human rights risks and how to address them.

The Commentary to UNGP 19 (right) makes clear that where a company does have the ability to prevent or mitigate an adverse impact caused by its business partner, it should do so. This is often most effectively achieved early in a business relationship, for example in contractual requirements, and as part of wider collaborations with other initiatives and actors.

If, as is often the case, it lacks the ability to make a positive change in the performance of a business partner, the company should make efforts to increase its leverage wherever possible. A common example of this kind involves providing capacity-building or other forms of support to the business partner to improve its performance, such as engagement programmes with farmers and growers to support farm productivity and promote certification. Providing such support may often be most appropriate in cooperation with other actors including other companies, NGOs, trade unions and/or governments where appropriate.

In other cases, commodity trading companies might lack leverage to impose human rights due diligence clauses (e.g. gold traders/refiners seeking to influence practices of multinational mining companies). As the Commentary to UNGP 19 states, “There are situations in which the enterprise lacks the leverage to prevent or mitigate adverse impacts and is unable to increase its leverage. Here, the enterprise should consider ending the relationship, taking into account credible assessments of potential adverse human rights impacts of doing so.” The box below gives OECD guidance on disengagement from business relationships:

OECD Disengagement With a Supplier

How should a commodity trading company think about disengaging from a business relationship when it finds that it lacks leverage to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts associated with the actor involved? When does it make sense to terminate a specific business relationship due to concerns over human rights performance?

There are a range of cases in which commodity traders may face such questions. For example, a commodity trader may discover that one of its business partners is involved in major abuses of basic labour standards concerning workers involved in producing a commodity which it buys on a regular basis. What should be done in such a case, in particular, when it is clear that there is limited or no ability to influence the business partner’s practices over time?

Equally important, companies must also take into consideration the issue of potential adverse impacts resulting from disengagement including loss of jobs for workers or other local economic impacts and seek to prevent or mitigate those potential impacts in cases where it is decided to disengage (see SOMO Should I stay or should I go?).

The UNGPs and OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises suggest that disengagement with a supplier is a last resort, either after failed attempts at mitigation or where the enterprise deems mitigation not feasible, or because of the severity of the adverse impact. The UNGPs and OECD Guidelines also note that determining how “crucial” a business relationship is to a company should be part of decisions concerning disengagement.

In this context, the UNGPs refer to products or services that may be “essential” and to those “for which no reasonable alternative source exists” but a number of other factors are also relevant in determining whether a business relationship can be considered crucial, including:

- volumes and relative proportion of the supply or investment for the company considering disengagement;

- duration of the relationship, both in the past and in terms of contractual commitments going forward;

- reputational interests.

The OECD Guidelines offer the example of “temporary suspension” of a relationship as a potential step during risk-mitigation efforts. Other potential disengagement steps could include scaling back purchase volumes or terminating parts of a multi-faceted relationship. Commodity trading companies will need to assess in such cases whether incremental disengagement strategies may be useful in increasing leverage over specific business partners and whether these or other steps may assist the company in making a business relationship less “crucial” over time.

Annex II to the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas includes a series of cases where implementers of the Guidance commit to immediately suspend or discontinue engagement with upstream suppliers where they identify a reasonable risk that they are sourcing from, or linked to, any party committing serious abuses. These include:

“Immediately suspend or discontinue engagement with upstream suppliers where the company identifies a reasonable risk that they are sourcing from, or linked to, any party providing direct or indirect support to non-State armed groups.”

Example Some Principles for More Just Business Relationships

[N.B. Such approaches may be commodity specific, however it it useful to examine practices in different areas to share learning and inform other initiatives. The below example relates to agricultural commodities.]

In his 2011 report on the right to food, the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food and the current UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty Olivier de Schutter outlined seven key elements that should be integrated into contracts and relationships between a trading company and supplier entities:

- Long term economic viability: Agreements should be structured so that both farmers and companies benefit and so that financial stress does not lead to one of the parties reneging on their obligations.

- Support for small-scale farmers in negotiations: To ensure that farmers who are in weaker bargaining positions have the opportunity to contribute to the wording of contractual provisions, farmers’ organisations may have a key role to play in supporting the negotiation of contracts and in providing advice.

- Gender equality: Contracts should not automatically be in the name of the male head of household or the holder of the title to the land cultivated. Instead, where the contract is entered into with a woman, it is her name that should be on the document.

- Pricing: Pricing mechanisms should incorporate production costs, risks and returns. The Special Rapporteur observes that while a variety of pricing models such as split pricing, fixed prices, spot market-based pricing etc exist, the idea mechanism is one which guarantees a fixed minimum price based on the need to meet production costs and ensure a living wage for all workers concerned. The prices paid by the buyer should be higher if market prices increase. This will guarantee a stable supply for the buyer while ensuring that small-scale suppliers can pay living wages to their employees;

- Appropriate structures to facilitate communication as well as the resolution of disputes;

- The promotion of agro-ecological forms of production that are environmentally sustainable;

- Encouraging farmer organisation by means of cooperatives, farmer associations or collectives.